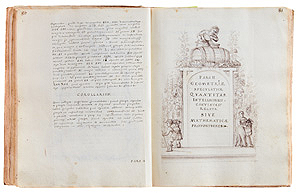

7: "PUNCTUM MINIMUM ET MAXIMUM GEOMETRICA DEI ET UTRIUSQUE MUNDI IMAGO".

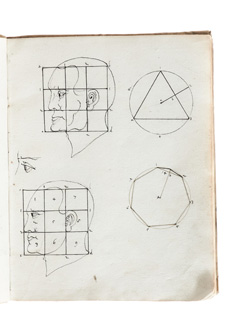

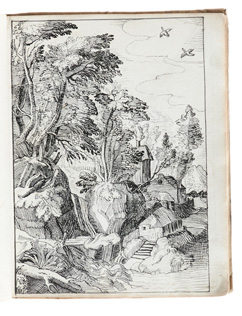

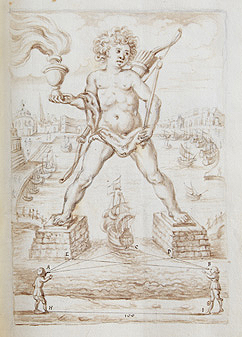

Sehr umfangreiches Lehrbuch der Geometrie und Kosmografie , wohl im Umfeld der Universität Dole durch einen gelehrten Minimen konzipiert und in einem Minimenkloster in Burgund hergestellt. Vermutlich handelt es sich um ein Widmungsexemplar für einen Fürsten oder eine hochgestellte Persönlichkeit an der burgundischen Universität in Dole. Die ungewöhnlich reiche und aufwendige Ausstattung, ausgeführt von geübter Hand auf hohem zeichnerischen Niveau, unterstützt diese These. – Der erste Band enthält ein Lehrbuch der Geometrie auf der Grundlage antiker Quellen sowie einen ausführlichen Teil zu ihrer praktischen Anwendung im Vermessungswesen. Der zweite Band ist der Lehre von den Himmelskörpern gewidmet.

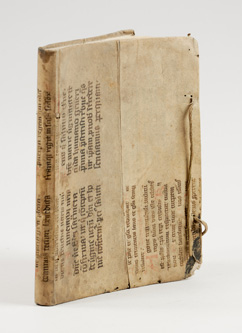

Die Entstehungszeit der beiden Werke lässt sich recht genau bestimmen, da als Tag der Vollendung des ersten Abschnitts der Geometria speculativa (Bd. I, S. 79, in der Schriftkartusche der letzten ganzseitigen Illustration) der 20. Juli 1644 angegeben ist. – Beide Bände stimmen im Format, im Schriftspiegel, in der feinen regelmäßigen Textschrift mit wenigen kursiven Elementen, in der Verwendung der Kapitalis für die Überschriften und auch im Stil der Illustrationen überein. Daher ist anzunehmen, dass die beiden Bände als sorgfältige Reinschriften eines lange vorbereiteten Konzeptes wohl ohne größere Unterbrechungen in relativ kurzer Zeit entstanden. Sie sind weitgehend, aber nicht zur Gänze vollendet. Die im Dekor etwas unterschiedlichen Pergamenteinbände wurden sicher bald nach der Einstellung der Arbeiten an der Handschrift angefertigt.

Beide Bände sind mit einer zeitgenössischen Paginierung versehen, die auch die weißen Blätter einbezieht. Die freien Seiten vor Beginn neuer Abschnitte sind aus der arbeitsteiligen, an der Gliederung ausgerichteten Herstellung zu erklären, so dass mehrere Hände gleichzeitig an den einzelnen Lagen schreiben konnten. Dennoch wurde das Manuskript nie vollständig fertiggestellt. Dies belegen einzelne Lücken im Text. So bleibt im ersten Band ein Kustos ohne Anschluss (S. 198), obwohl die nach einer Bildseite (S. 199) folgenden Seiten 200 und 201 weiß sind. Auf vorgesehenen, jedoch nie eingetragenen Text lassen in Band I auch die weißen Blätter zwischen den illustrierten Titeln der letzten beiden großen Abschnitte (Teil III und IV der Geometria practica) und dem Beginn des Traktates schließen. In mehreren Fällen gibt es allerdings Sprünge in der Paginierung, die auf nachträgliches Entfernen von Blättern, jedoch nur zum Teil unter Textverlust, schließen lassen (in Bd. I fehlen die Seiten 185/186, 249-252 und 313-316, in Bd. II die Seiten 31/32, 79-86, 93-100 und 147-156).

Unsere Beschreibung der Handschrift stützt sich auf umfangreiche Vorarbeiten von Ivo Schneider, Professor für Wissenschaftsgeschichte, und Menso Folkerts, Professor für Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften; beiden Mathematikhistorikern danken wir an dieser Stelle für ihre wertvolle Hilfe. – Ausführlichere Beschreibung auf Anfrage.

Very comprehensive textbook on geometry and cosmography in two volumes. – The first volume contains a textbook of geometry based on ancient sources and an extensive part to their practical use in surveying and mapping. The second volume is dedicated to the science of celestial bodies. – Although the author of the extensive textbook which is compiled with the knowledge of antique and contemporary theories, cannot be named, probably an erudite member of the Order of Minims, the manuscript can very likely be associated with the university at the Burgundian Dole. The traditional geocentric model is firmly defended against more recent observations and theories. The metric introductions in the first volume are of special value as independent texts. A more precise analysis of those might provide information regarding the origin and writing of the manuscript. The connection that exists with the teachings of the mathematician and Minim Marin Mersenne mentioned several times in the text, would need an in-depth examination also. Our text shows a vehement rejection of astrology. – Especially the programmatic content of the metric introductory poems, partly with explicit reference to the Order of the Minims or to the freedom of Burgundy might shed light on the background of the origin of the lavishly designed textbook by a more precise investigation. It is probably a presentation copy for a prince or a high-ranking personality at the Burgundian university in Dole. This thesis is supported by the exceptionally rich and lavish layout, designed in close connection with the text and executed on a high graphic level by an expert hand. – The time of origin of the manuscript can be determined quite accurately, as the 20th of July 1644 is indicated as the day of completion of the first paragraph of "Geometria speculativa" (Vol. I, p. 79, in the inscription cartouche of the last full page illustration). – Both volumes correspond in format, text layout, in fine regular text script with few italic elements, in the use of capital letters for headings and also in the style of the illustrations. Therefore one can assume that both volumes were developed as meticulous clean copies of a long in advance prepared concept, in a relatively short time, probably without major interruptions. They are largely, but not entirely completed. The free pages at the beginning of new paragraphs can be explained by the structure, so that several hands were able to write simultaneously at the particular quires. – The blank leaves in vol. I between the illustrated titles of the last two large chapters (part III and IV of "Geometria practica") and the beginning of the treatise may suggest a scheduled but never inscribed text. The differently decorated vellum bindings were probably made soon after finishing the manuscript. Both volumes are paginated by contemporary hand, also including the blank leaves. The skips in the pagination indicate that after binding some leaves had been removed (lacks pp. 185/186, 249-252 and 313-316 in vol. I, in vol. II pages 31/32, 79-86, 93-100 and 147-156 are missing). – Our description of the manuscript is based on extensive preliminary work by Ivo Schneider, professor of history of science, and Menso Folkerts, professor of history of natural sciences; at this point we would like to thank both historians of mathematics for their valuable assistance. – In-depth description on request.